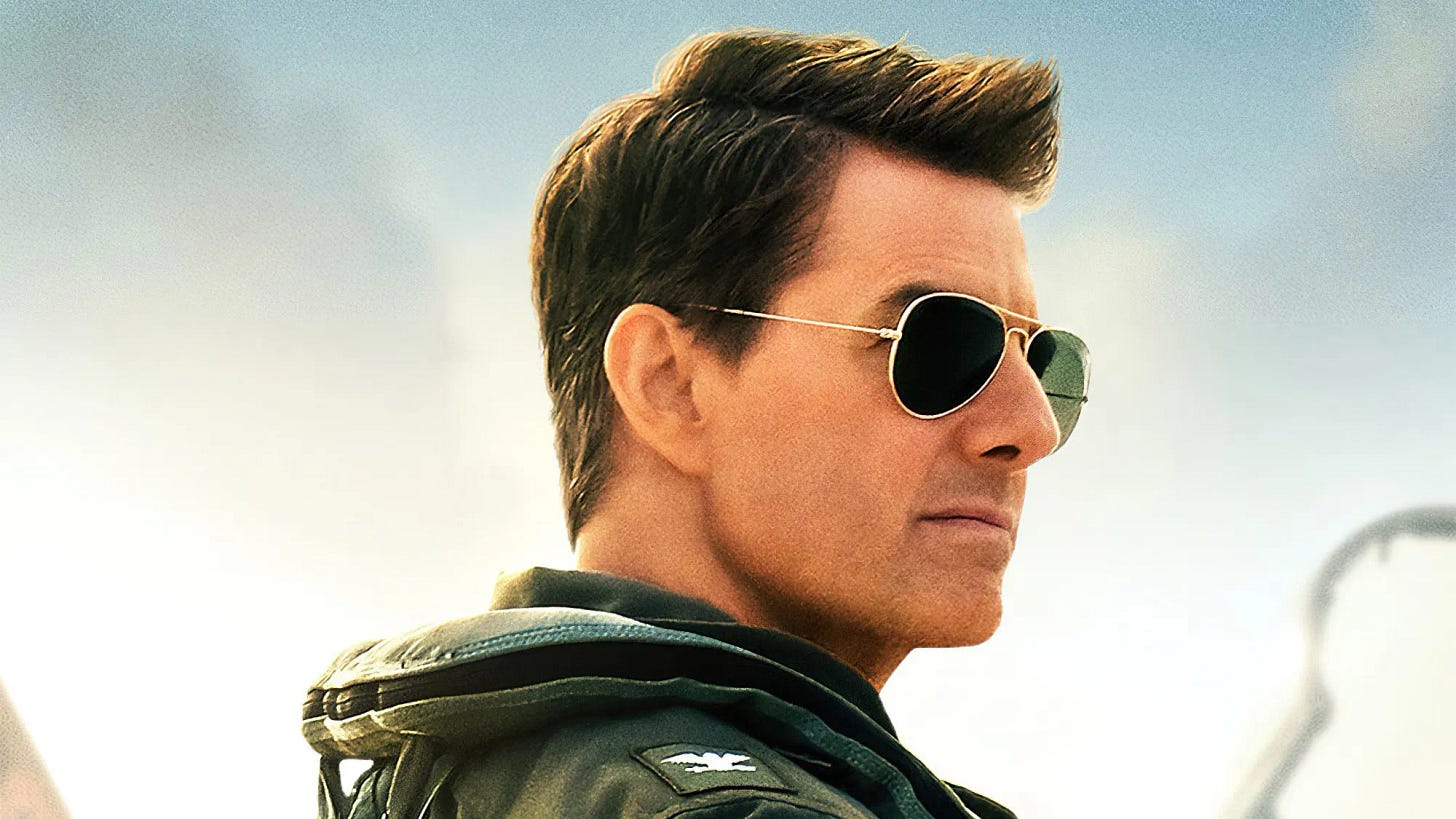

Tom Cruise, Forever—Our Deepfake Dystopia

The purveyors of AI know what fiends for nostalgia we are

Picture the year 2066. We let our apartment’s supervising AI, “Sia”, know that we’re heading to the theatre. A few things are playing, but the news of a developing ‘cyberwar’ has stressed us out, so we’re in the mood for something cathartic. At the theatre, we have half demolished our popcorn in anticipation by the time the trailers end. The director’s name flashes up first, and then:

Tom Cruise as Aiden Colt.

Tom Cruise. Tom Cruise? Isn’t he dead? Didn’t he die about twenty years ago? But before we can follow that thought any further – he’s on screen. Tom Cruise is panting heavily after having climbed up the side of a shipping container and we are damn sure he is dead. And yet, this film released just this week. His hair is long, flowing, just like in Mission: Impossible 2, and that’s when a headline from recent memory floats into our subconscious.

Deepfake Film Reintroduces Posthumous Heartthrob Tom Cruise to the Silver Screen

A minimally paid stuntman towers above us, his face digitally redrawn with that of the now perpetually renowned action hero, Tom Cruise.

I.

First, the legal implications.

When Tom Cruise dies, who will retain ownership of his likeness? His family? The Church of Scientology? As it stands, no broad agreement exists on post-mortem rights of publicity. Film studios have therefore played it safe, only implementing deepfake technology where the original actor is also present in the film. See the new trailer for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny for a recent example. But such restraint could be poised to change, and I trust Disney to be the fastest and fattest vulture.

The Walt Disney Company is a conglomerate built on copyright. So much so, that they’ve lobbied not once, but twice, to extend copyright terms for their famous properties. But with the House of Mouse losing the mouse himself to the public domain in 2024, hoarding nostalgic faces could be the new direction they need. Instead of old films with new actors, we’ll get new films with old actors.

Out with remakes, in with deepfakes.

After all, consider the current alternatives. Hollywood’s regular raid of the Beverly Hills retirement village has seen them wheeling out the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger for Terminator at the spry age of 75, and Harrison Ford for the aforementioned Indiana Jones sequel at 80. Not a permanent solution by any means.

Alternatively, Hollywood could find someone new, relatively unknown, and slowly build them up to an equivalent level of fame. But at what cost? How many well-written, expensive and successful films would a new action hero have to star in, before they even approached the box office bankability of Tom Cruise? Five? Ten? And even then, they wouldn’t be Cruise.

They wouldn’t be this guy.

But the deepfake future is more than cost-effective, it’s safe.

Since the death of DVD retail, Hollywood is more anxious than ever about actually making their money back. They own nostalgic properties, yes, but without the actors associated with the original material, re-monetisation of those franchises poses a serious challenge. Paul Walker, for example, is so entrenched in the audience’s memory of the Fast and Furious franchise, that director Justin Lin discussed digitally reviving his corpse for the tenth film in the franchise, Fast X.

And this is how the deepfake film ushers in the safest iteration of cinema yet. No more recasts, no more death. No more ageing actors forcing screenwriters to shoehorn time travel into their franchise. No more scheduling conflicts. No more inconvenient overdoses, nor sexual misconduct dashing trilogy plans. No more controversial political stances spoiling merchandising opportunities. The software renders the body double faceless, which in turn ensures they remain nameless and devoid of all negotiating leverage. This is the reliability of working with software. A software cannot age or die. A software cannot unexpectedly get too obese for direct sunlight.

A software cannot say ‘no’.

Even for the final crop of A-list actors, the deal works out. After lending out their likenesses, they’ll bid farewell to green screens and keep to the more dignified pastures of activism and award ceremonies. Only the next generation of actors and actresses will suffer, but we won’t know their names so as to mourn their loss. After all, why would studios invest in a young and attractive up-and-comer, when they can simply scan in pre-surgery Megan Fox?

Of course, we could say no to all of this. We could walk out of that theatre right now. We could ask our digital companion back home to instead read aloud this week’s trivia quiz, as we reconstitute premium protein packets and sprinkle on a sachet of ethically sourced, carbon neutral, and wholly unidentifiable flavouring.

But would we?

II.

Let’s look at the data. After all, perhaps our viewing habits are a victim of circumstance. Perhaps we are forced to consume these regurgitations due to factors outside of our control. For a little insight into our own nature, let’s look at music. From The Honest Broker, emphasis mine:

Old songs now represent 70 percent of the U.S. music market, according to the latest numbers from MRC Data, a music-analytics firm. Those who make a living from new music—especially that endangered species known as the working musician—should look at these figures with fear and trembling. But the news gets worse: The new-music market is actually shrinking. All the growth in the market is coming from old songs.

Is Old Music Killing New Music?

Ted Gioia

Left to our own devices, we, collectively, are choosing to go back through the musical catalogue. We are choosing Tupac over Doja Cat at an increasingly alarming rate. If the trend continues, we will feasibly reach a time when new music will be entirely suffocated by old music. If new music is made, no one will listen to it. Even if some of us do, we will be such a relatively minuscule audience that it won’t be economically viable for those artists regardless.

‘New’ is also a relative term.

From the perspective of the individual, the discovery of good, old music is no different to the discovery of good, new music. After all, if it’s new to us – does it matter if it’s not really new at all? Arguably, we’re at this point already. Spotify boasts over 80 million tracks at the time of writing. At a very conservative estimate of two minutes per song, if we listened to sixteen hours’ worth of music every day from the moment we were born, we’d still barely eke out maybe a fifth of the 457 years that we would need to cover humanity’s entire preserved discography.

And if we don't want new musicians, why would we want new actors? Maybe we are perfectly content with Tom Cruise, forever. In fact, while we’re here, pick your era. Perhaps rugged Old Man Cruise is not your style. I see you. You're the discerning viewer. We've got you covered. We will find the correct Cruise to get your engine running. What about Risky Business-era Cruise?

Why stop there?

Who else should our sentimentality rescue from a legacy merely immortalised in the body of work they produced during their natural life? What about our favourite podcast host? With some AI magic and enough sample data, we can already emulate folks like Joe Rogan with disturbing accuracy. Sure, that is ‘only’ his voice and appearance, but AI is already writing full novels and responding to complex queries in natural language. Soon the empty digital soul of Joe Rogan will riff on news topics for the rest of internet eternity.

Maybe you don’t like Joe Rogan. Maybe you don’t like the idea of Tom Cruise as Rocky Balboa in the 2049 remake of Rocky. That’s alright. We will stream straight to your living room that same film, but starring Jackie Chan instead. Or Sasha Grey. Or Mussolini. Why not? Snapchat’s filters already map, model and shape faces live and in front of us with whatever design we choose. Give a studio the near-future evolution of that technology, the budget, and nine months of skilled CG technicians working on it – and we’ll get whatever weird romances we want, with all the convincing subtleties of actual acting talent performed by the software.

We want this. The studios want this.

What could go wrong?

III.

Frankly, we might worry about the removal of people from the creation of entertainment. Entertainment already walks an impossible balance between being both art and product. Part of why it, at least, sort of works, is because the people working on it, despite all efforts to the contrary, still manage to seep a little of their personality – their artistic intent – into the final product. The more we strip people out, the less of a soul in the end product.

We’ve already seen what can happen when algorithms become directors. These unsettling remixes of content exist devoid of intent, instead informed only by market trends. As exposed in the strange case of Youtube Kids, the results are non-sensical, unnerving, and often implicitly violent:

Ultimately, if we choose to consume nothing new, we’ll also create nothing new. At which point, technology’s grand replacement of mankind may be final, as AI feeds back to us the digital mincemeat of our own history. Historians of a future civilisation will sift through the rubble with confusion. At some point in the mid-twenty-first century, the enduring record of mankind’s evolution, as recorded by our artistic output, appears to end. The soul of the entertainment industry – already just a nervous, flickering pilot light – will finally have been snuffed out. Perhaps a death knell for society’s own collapse.

Or?

Or I'm a pessimist, and after a few decades of watching deceased Chris Hemsworth’s Thor confuse himself with Earth’s customs for the thirty-eighth film in a row, we’ll say ‘enough’. We’ll demand better from Hollywood, and they will acquiesce. Producers will show restraint, relegating deepfakery to tasteful, creatively compelling use, rather than as a cheap trick to get our Memberberries tingling.

And if that doesn’t happen, maybe something else will save us. Perhaps another Carrington Event will occur, and the sun’s sudden lashing of solar flares will rescue us from that stagnant, digital bath in a flash of sizzling electrics. A hard reset. The four hundred-year reboot that our franchise needed.

On that day, Tom Cruise won’t be there to save us. But he’ll be with us in the only place we ever truly needed him. In our hearts. In our fond memories of A Few Good Men and Jerry Maguire. The most salient of his films might be passed on, generation to generation, through spirited retellings around a campfire of burning tyres, their moral lessons etched into our lineage. Tom Cruise. Not a soulless, digital husk, perpetually at the edge of tomorrow, but living folklore. An oral history of his triumphs. The life of Tom Cruise. The legend of Tom Cruise.

Tom Cruise, Forever.